“THE rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, He made them high or lowly, And ordered their estate.”

So goes an oft-omitted verse of the famous hymn, All Things Bright and Beautiful.

It’s a truly horrific set of words, outlining how the oppressive, class-based system of the mid-19th century – complete with desperate poverty imposed by the rich owners of land and industry – was pre-ordained.

Those at the top of the tree were put there by God no less, with the poor ‘at their gate’ – and never would it change.

No wonder this part of the hymn is largely ignored and widely forgotten. It deserves to be.

However, at the time it was first written down, all things were not bright and beautiful in England and indeed, in Europe.

The French Revolution, in the late 18th century, had spooked ‘the rich man’, who was contemplating that perhaps he was not safe ‘in his castle’ and the ‘poor man’ would not always be content to stay restrained by ‘his gate’.

Europe had been made aware, in the most gruesome way, that change could indeed happen.

So the rich man was frightened, and the need was widely expressed that Britain – should it wish to avoid the fate of France – should crack down on any perceived notions of the poor man seeking some sort of improvement in their lot which could put the ordained class structure in jeopardy.

It was into this atmosphere a young Dorset man, James Frampton, came of age.

Born in 1769, at the ripe old age of 15, young James inherited the family’s 9,000-acre Moreton Estate and the family seat, Moreton House itself.

James was an exemplary ‘conservative’, but then, why wouldn’t you be, when you are pre-ordained to own half the county?

James Frampton

In 1791, aged 22, following the obligatory upbringing of an upper-class boy; private-school education (Winchester), followed by university (St John’s College, Cambridge), he embarked on another upper-class right of passage – the Grand Tour – which saw rich young men travel around Europe to see how other rich people lived.

However, throughout his trip, James would have been in no doubt about what was happening in France.

The storming of the Bastille had occurred in 1789 and the struggle for power was continuing as James enjoyed living the high life in various European capitals.

The French Establishment was under siege – and on its way out – which must have been concerning for an English conservative so bound by his own societal role – and so committed to the preservation of it.

Eventually, James returned to his estate. And we can assume he was of the mind to do everything in his power to preserve the status quo – as it maintained his wealth, status and entitlement.

To do so, he embarked on a life of ‘service’ (though the 18 servants at Moreton House might argue with his definition), including as High Sheriff of Dorset, later a Justice of the Peace, and a magistrate, a role he was to occupy for some six decades.

From Moreton House, he watched on in horror – like many of his contemporaries – as the French Revolution he had himself seen years earlier was now turning extremely bloody.

Moreton House, home of the Frampton family. Picture: Mike Searle

His concerns over the English Establishment would again have been at the forefront of his mind.

‘The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, He made them high or lowly, And ordered their estate.’

On February 24, 1834, farm labourer George Loveless left his cottage ahead of day labouring on a Dorset farm, bidding farewell to his wife, Betsy, and their three children.

Little did 37-year-old George realise he would not see them again in private for three years.

For that day, a warrant was issued for George’s arrest. His crime? Well, George wanted a pay rise and, along he and a few friends an colleagues, they had decided to ask for one – together.

Now, to understand why George – along with his brother James, James Hammett, James Brine, Thomas Standfield and Thomas’s son John – had decided to pursue an increase in their pay, it is important to have some context as to how life was in Dorset in 1834.

Before the six united to form a group in the village of Tolpuddle, the British gentry had already been unsettled by an uprising among the workers they exploited.

In 1830, agricultural workers in the east of England responded to the mechanisation that was replacing their labour – and the inhumane conditions they were forced to endure.

The action – dubbed The Swing Riots – spread across much of the south of England and was the largest movement of social unrest of the century.

One participant in the Swing Riots was George Eavis, a relative of one Michael – the founder of the Glastonbury Festival – who continues to farm in Somerset, of course.

To this day, in the Woodsies area at Glastonbury, a fire is lit each night (and burns throughout the year to warm villagers). It’s name is the Tolpuddle Fire, in honour of George Eavis, George Loveless, and their comrades.

The Tolpuddle Fire at Worthy Farm, home of the Glastonbury Festival, in honour of the martyrs and their contemporaries. Picture: Paul Jones/Somerset Leveller

Anyway, in 1830, the Swing Riots highlighted restrictive actions of the church, including tithes; the lacking representation of poor people in law; and rich tenant farmers and landowners (such as James Frampton) who exploited their labour and imposed the harsh working conditions.

The Establishment, as you would imagine, responded with extreme force in a bid to nip such action in the bud. The oiks were getting rowdy and needed to be firmly dealt with.

Around 2,000 protesters were tried over the Swing Riots. More than 250 were sentenced to death – although ‘only’ 19 were hanged – while 644 were jailed and 481 transported to Australia, which may as well have been a death sentence, but more on that later.

Yet there was no stopping change. The industrial revolution was underway, meaning farm labour was declining as the machines took over – doing the work of dozens of men – which was embraced by the elites; the landowners and the squires. However, what they refused to embrace was the way this changed people’s lives. They accepted the increased profits the industrial revolution brought, but refused to accept any change to their role in caring for the poor.

As a result, the ‘worth’ (pay) of workers decreased, and poverty flourished, provoking responses like the Swing Riots. The Establishment was facing some rebellion and it was happy to shut it down, by any means necessary.

But at the other end of the spectrum, largely ignored by James and his ilk, conditions for the poor – were unsustainable.

A Board of Agriculture report of 1812 gives a good summation of dietary conditions faced by many, saying: “The food of the poor is wheaten bread, skimmed milk cheese, puddings, potatoes, and other vegetables, with a small quantity of pickled pork and bacon. In some parts of the Vale of Blackmoor, the peasantry eat very little besides bread and skimmed milk cheese.”

And in 1843 – the year George Loveless left his home that February day – a Commission into the ‘Employment of Women and Children in Agriculture’ visited nearby Stourpaine – and found some horrific stories.

The report detailed “a cottage in which 11 persons slept in three beds without curtains in a room 10 feet square; the father and mother with two infants in one bed; two twin daughters of 20 and a third of seven years old in another; and four sons, aged 17, 15, 14 and 10 in the third”.

These were hard times – and George and his five comrades thought they deserved better. And they did.

But the reality was, rather than things improving, they were facing a cut in their wages and conditions, if such a thing were possible.

Landowners, you see, had cottoned to economies of scale, which meant the larger your estate, the fewer people you need to run it, per acre. And the technological advances attacked in the Swing Riots meant they could do more with less, so they did what companies still do today – they consolidated, used new technology to do the work and discarded people.

The wealthy estates grew, while jobs and wages fell.

Often, workers had little choice but to accept. There was no welfare state, no real safety net, so they were often forced to accept these cuts in terms and conditions, despite the devastating impact on their lives.

But George and his friends were determined not to allow this enhanced poverty to be enforced on them, their comrades, or their families, so decided to campaign against it and call for better wages and conditions.

Together, they formed the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers and called for their wages to be increased – not reduced to levels far below what we would call the poverty line.

The group met at Standfield’s cottage to discuss their efforts, or in a room at the small Methodist Chapel in the village.

The Tolpuddle Methodist Church where the martyrs met. Picture: Google

But to avoid the wrath of Frampton and his ilk, they kept these meetings secret, so they eventually began gathering somewhere their light would not attract attention – beneath a sycamore tree on a green in Tolpuddle.

Why was secrecy so important? Remember the French Revolution and the fear it provoked in the ‘rich man in his castle’? Well, the English weren’t about to allow something like that happen here.

One way the Establishment hoped to prevent further uprisings was by, basically, making it extremely difficult to form what we would call a ‘union’ – to collectively bargain, as it’s known.

One thing banned – under the Combined Acts in 1799 and 1800 passed in Parliament – was the ‘combining’ (organising) of workers in labour disputes using any sort of secret pact.

Unfortunately for George and his friends, they had sworn an oath to stick together – and not told anyone about it.

George and his friends decided, for their own safety, to keep their pledge a secret – and in doing so, committed a crime.

When James Frampton heard whispers of a group ‘combining’ on his estate – the estate he had worked hard (by being born) to inherit – we can only imagine how angry and frightened this made him feel.

He had been in Europe as the French Revolution started, don’t forget, so knew what could happen if poor people started organising effectively.

In his bid to preserve the England he so loved and ensured he would forever remain rich and privileged, Frampton set out to quash this act of rebellion by a group of poor labourers.

But he could not simply have George and his cohort arrested for organising – which is where the oath of secrecy came in. The group’s secret oath, that bound them so loyally in their efforts, was their downfall.

The Tolpuddle Martyrs (clockwise from top left); James Brine, James Hammett, James Loveless, John Standfield, George Loveless and Thomas Standfield

The resulting brutality of their treatment by the justice system is a clear indication of just how determined the Establishment was to snuff out any sort of ‘rebellion’ by workers. To quash this desire for dignity.

There have been attempts to present Frampton merely as a conservative, keen to preserve the great British society of the time, as someone who was not responsible for what happened to George and his friendly society.

I don’t buy this. Agricultural workers were living in extreme poverty, working in inhumane conditions for paltry reward – reward that was being cut even further by unscrupulous landowners and squires like Frampton.

This was no act of patriotism. For how could one claim to love their country while allowing such horrendous poverty on their doorstep?

This was not conservatism, it was self preservation on a massive and brutal scale. Frampton knew what would happen.

And the way George and his comrades were treated puts this beyond doubt; They were made an example of, as the Swing Rioters had been before them.

Their guilt and intentions were never in doubt, and they were promptly sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

Just three months after saying goodbye to his family that February morning, George was aboard the William Metcalfe, heading for Australia – expected never to return.

Transportation – which meant being taken to Australia – was a brutal punishment, effectively a death sentence.

Convicts were slaves when they reached the southern hemisphere, often worked to death long before the end of their sentences.

George would have expected never to see his family or his homeland again.

“To enumerate the various miseries and evils which prisoners are subjected to from the time of landing in the colony until their death, would be utterly impossible; suffice it to say it is dreadful in the extreme, so much so that a person who has never been there can have no idea of it,” he wrote of his transportation.

And upon arrival, things only got worse, as fellow Tolpuddle comrade, James Brine, wrote.

“I was employed to dig post-holes (but) having walked so far without shoes, my feet were so cut and sore I could not put them to the spade,” he said. “I got a piece of an iron hoop and wrapped round my foot to tread upon, and for six months I went without shoes, clothes, or bedding, and lay on the bare ground at night.

“Shortly afterwards I was sent to the pool to wash sheep, and for 17 days was working up to my breast in water.

“I thus caught a severe cold, and having told my master that I was very ill, asked him if he would be so good as to give me something to cover me at night, if it were only a piece of horse-cloth.

“‘No’, said he, ‘I will give you nothing until you are due for it. What would your masters in England have had to cover them if you had not been sent here? I understand it was your intention to have murdered, burnt, and destroyed every thing before you, and you are sent over here to be severely punished, and no mercy shall be shown you’.”

No mercy for trying to negotiate a pay rise.

However, in a poignant homage to the efforts of the French working class, George and his comrades honoured their illegal oath. They did not give up – instead, they stayed fiercely loyal to the aims of the workers.

“We raise the watchword, liberty. We will, we will, we will be free!” wrote George.

Back at home, the Tolpuddle gang’s plight had received a lot of attention – a rarity for such disputes, particularly in rural areas like Dorset and involving so few workers.

But such was the injustice of the Tolpuddle group’s treatment and sentences, they provoked fury among the working class – who themselves were facing a similar situation.

In March 1834, a Grand Meeting of the Working Classes to discuss the case, called by the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, was attended by more than 10,000 people and the London Central Dorchester Committee was formed to campaign for the men’s pardon.

A petition challenging their sentences gained 800,000 signatures, and in April that year, around 100,000 people assembled near King’s Cross to demonstrate their plight.

In response, the scared Establishment armed itself. The government ordered lifeguards, the Household Cavalry, detachments of Lancers, two troops of Dragoons, eight battalions of infantry and 29 pieces of ordnance or cannons were gathered, with more than 5,000 special constables sworn in to guard against the workers demanding a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.

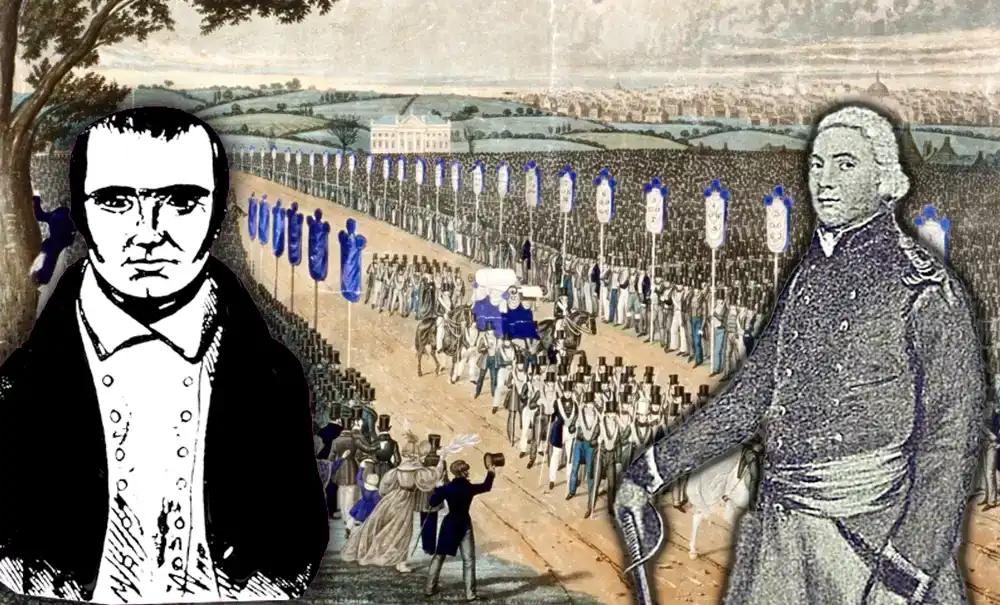

The 1834 Tolpuddle demonstration at Copenhagn Fields in Islington, London, as depicted by artist W Summers

The gate was struggling to keep the poor man from the castle – so it was fortified. Indeed in Dorset, Frampton barricaded his own castle – Moreton House – to protect from any upheaval from workers who might dare to breach the border of their god-given poverty; His gate.

In Australia, the six Dorset farm workers were largely unaware of what was happening in Britain – unaware they had become known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Unaware fledgling unions were supporting their families and championing their cause – and unaware it was working.

Eventually, 10 months after the martyrs had been sent to Australia, the Establishment was forced to cave.

By June 1835, Lord John Russell, the Home Secretary, had tried to issue the men with conditional pardons, but this was not enough for the campaigners and the Tolpuddle Martyrs at this point refused to accept compromises.

So it was that on March 14, 1836, they were granted a full and free pardon.

The six farm workers from the tiny Dorset village of Tolpuddle were going home – as free men.

George set foot on British soil again on June 13, 1837.

There was no raucous welcome, no celebration. He returned to Dorset and wrote an account of his experiences – and of the mistreatment of workers – entitled The Victims of Whiggery, which is still available today.

James Loveless, James Brine, Thomas and John Standfield arrived home on March 17, 1838 – exactly four years after their trial – and received a celebratory welcome from the people of Plymouth.

James Hammett, the last of the martyrs to return, arrived in August 1839. He was given a public welcome the following month at London’s Victoria Theatre – now known as the Old Vic.

In honour of their plight and their efforts on behalf of the working class, The London Dorchester Committee bought each of the six a lease on farms in Essex; farms where they could live by their values into their old age…

But this was not to be. The Establishment was not about to allow such a threat to remain.

In Essex, landowners and others of prominent standing – like Frampton before them – refused to accept George and his friends’ views, that might bring into question their status and wealth.

“George Loveless, instead of quietly fulfilling the duties of his station, is still dabbling in the dirty waters of radicalism and publishing pamphlets to keep up the old game,” wrote The Essex Standard.

The martyrs had forced some progress, but the upper classes were determined not to go without a fight. They believed, as in All Things Brght and Beautful, they were born to rule – ordained by God – and any effort to change that was to bathe in the ‘dirty waters of radicalism’.

The Vicar of Greensted, preaching against the martyrs’ chartist beliefs (remember this tithes?) said the foundations of decent society were being undermined by the martyrs’ beliefs in fairness. Paternal, beneficial order where everyone knew his proper place must be restored, he said.

The rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate.

Eventually, pressure finally told, and the martyrs relented. Five of the six sought new lives in Canada, where they settled as farmers in London, Ontario.

But what of the sixth, one James Hammett?

Each year, in February, a wreath-laying ceremony takes place at a small, unimposing grave in Tolpuddle.

In 2025, chair of Dorset Council – Cllr Stella Jones MBE – and High Sheriff of Dorset Anthony Woodhouse (one ponders what one of his predecessors, one James Frampton, would think?) were in the village to enjoy a tour of the recently-renovated Tolpuddle Old Chapel – home to early meetings of six farm workers determined to improve their lot.

Then, a wreath was laid at the grave, in the St John the Evangelist Churchyard.

Alongside the pair were dignitaries including Honorary Alderman Pauline Batstone, founder and chair of the Tolpuddle Old Chapel Trust, Andrew McCarthy, and trustee and chair of the Trust, Professor Philip Martin.

They laid tributes at the grave of James Hammett.

Chair of Dorset Council, Cllr Stella Jones, and the High Sheriff of Dorset, Anthony Woodhouse, at James Hammett’s grave in Tolpuddle. Picture: Dorset Council

Hammett was the only martyr to return to Dorset. Perhaps understandably, he turned his back on agricultural work, and became a builder’s labourer.

He never wrote of his experiences; his trial, transportation and fame as, in his own way, a key member of a small revolution.

His gravestone simply reads: “James Hammett. Tolpuddle martyr. Pioneer of trades unionism, champion of freedom. Born 11 December 1811. Died 21 November 1891.”

George Loveless passed away in 1874 on his farm at Siloam, in Canada. He was survived by his wife Elizabeth and five children. He is buried at Siloam cemetery – alongside fellow martyr, Thomas Standfield.

James Frampton died in 1855. He is buried at St Nicholas Church, in Moreton, Dorset.

Today, the Tolpuddle Old Chapel Trust works to preserve the martyrs’ legacy in the village. With support from Dorset Council, The National Heritage Lottery Fund, Historic England, and 11 other funding bodies, the renovation and extension of the old chapel were completed in September 2023.

As many of us will know – and many do around the world – the small Dorset village of Tolpuddle has become a beacon for the labour movement.

Thousands visit the town each year to find out more about George, James, and their fellow martyrs. Annual festivals have been running in the village for decades, with commemorative events dating back to at least 1875.

Jeremy Corbyn speaks at the 2015 Tolpuddle Festival

In 1934, Lloyd George, then-leader of the Liberals, laid a wreath, and the festival has gone on to welcome a raft of performers and politicians, including the likes of Bill Bragg, as well as record crowds to hear then-Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn.

Tolpuddle remains a place of pilgrimage for the movement. It is a symbol of the struggles of working people around the world, seeking a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.

Now, in the 21st century, people are facing a similar struggle to that confronted by George and his group. Technology is once again set to reform the labour landscape, to drastically reshape the roles and lives of working people.

We should learn from history – from the experiences of the Swing Rioters and the Tolpuddle Martyrs – and never forget their efforts on behalf of working people.

For it is possible for those providing the labour to be provided with a comfortable life. Preserving, or creating, gross inequality is not laudible. It is not pre-ordained.

God did not order anyone’s estate.

The rich man is in his castle only because of the labour of that poor man at his gate – and he would do well to remember it.

And the sycamore still stands.

“We raise the watchword, liberty. We will, we will, we will be free.”

PAUL JONES

Editor in Chief

The sycamore tree in Tolpuddle, under which the martyrs met. Picture: Google

NOTES:

The usual caveats to this apply – I don’t see the tale of the Tolpuddle Martyrs as a difficult moral dilemma. They were right, the system was wrong. Yes, it’s a political incident in many ways, and brought about huge political changes, but perhaps more importantly it is simply a very human struggle for dignity – of right and wrong.

If opposing the horrific conditions George and his fellow martyrs – and millions like them – were being forced to endure is a political belief or ideology, then so be it. But that is not the main intention of this piece.

I would hope those on all sides would agree what happened then – and still happens now – was and is wrong, and needs to be addressed, particularly in the world of AI and continued technological advances.

If you want to contact me about this piece (or any others), please do, via paul@blackmorevale.net (please keep it civil!) – and links to some other opinion pieces are below.

Meanwhile, some very useful places to find out more about the Toldpuddle Martyrs that helped with this piece can be found at:

An excellent article detailing historical documentation of poverty in Dorset in the 19th century is available at johnmartinofevershot.org/the-state-of-dorsets-poor.

Another invaluable website telling the story of the Tolpuddle Martyrs and detailing current activities is at www.tolpuddlemartyrs.org.uk.

You can buy George Loveless’ The Victims of Whiggery HERE.

A somewhat bizarre piece attempting to mitigate the actions of James Frampton (and his ilk) was published in 2013, available at dorsetlife.co.uk/2013/07/frampton-hero-or-villain. The answer, for me, is pretty clear; even if you don’t count Frampton himself a villain, they system most definitely is.

A nice document detailing the annual Tolpuddle Pilgrimage – which started with a group walking from Stroud in Gloucestershire to Tolpuddle in 2015 – is available HERE.

There are also numerous podcasts and books about the Tolpuddle Martyrs available – have a Google around.

And if you care to read some of my other opinion pieces:

- OPINION: 90s toy crazes – and how the Teletubbies damaged children’s ‘moral lives’

- OPINION: The horrific story of the Chagos Islands – and Britain’s role in it

- OPINION: Why Facebook fact-checking can be a life or death matter…

- OPINION: Introducing Joshua N Haldeman, Technocracy, and a frightening idea

- OPINION: Do our dogs actually love us, really?

- OPINION: Climate change, denial, scepticism – and a 70-year-old warning

Leave a Reply